Alabama Claims Arbitration 1872, in John Bassett Moore (ed.), History and Digest of the International Arbitrations to which the United States has been a Party, 1898

See for the history of the CSS Alabama: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CSS_Alabama and http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-973

See for the History of modern inter-state arbitration between the US and Great Britain the contribution by King/Graham in AAA (ed.) Dispute Resolution Journal, January-March 1996, at 42 et seq.

For the lenthy full-text of Sir Alexander Cockburn's dissenting opinion see www.trans-lex.org/262138

See for further information: Paulsson, Jan, The Alabama Claims Arbitration: Statecraft and Stagecraft, in: in Franke/Magnusson/Dahlquist (eds.), Arbitrating for Peace, How Arbitration Made a Difference 2016, p. 7 et seq.

For a short documentary about the history of the CSS Alabama see this video by Discerning History

See also:

Veeder, The Historical Keystone to International Arbitration: The Party-Appointed Arbitrator - From Miami to Geneva, in: Caron/Schill/Smutny/Triantafilou (eds.) Practicing Virtue, Inside International Arbitration, 2015, at 127 et seq.

William Park & Bruno de Fumichon, Retour sur L’Affaire de L’Alabama: De l’Utilité et des Limites de l’Histoire du Droit, 2019 Revue de l'Arbitrage 743 (2019).

[The Alabama in the roads before Cape Town's famous Table Mountain in August 1863.

See also the handwritten testimonial of August 14, 1863 by Captain Semmes to the excellence of the services of the firm who supplied the Alabama during her stay in Cape Town. (Photo and PDF received from the Arbitration Foundation of Southern Africa)]

[Captain Raphael Semmes, Alabama's commanding officer, standing by his ship's 110-pounder rifled gun during her visit to Cape Town in August 1863. His executive officer, First Lieutenant John M. Kell, is in the background, standing by the ship's wheel.]

["Sunday Showdown" Painting by Tom W. Freeman; cf. the personal report by the captain of the Alabama of the encounter with USS Kearsarge on June 19, 1864 off the coast of Cherbourg, France.]

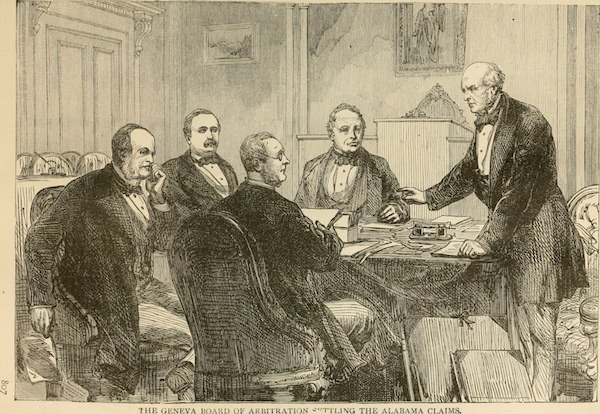

[This text is taken from: John Bassett Moore (ed.), History and Digest of the International Arbitrations to which the United States has been a Party, 1898, at 653 et seq. See for a historic view into the "Alabama Room of the Townhall of Geneva ".]

DECISION AND AWARD

Made by the tribunal of arbitration constituted by virtue of the first article of the treaty concluded at Washington the 8th of May, 1871 between the United States of America and Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Recital of provisions of the Treaty of Washington

The United States of America and Her Britannic Majesty having agreed by Article I. of the treaty concluded and signed at Washington the 8th of May, 1871, to refer all the claims 'generically known as the Alabama claims' to a tribunal of arbitration to be composed of five arbitrators named:

One by the President of the United States,

One by Her Britannic Majesty,

One by His Majesty the King of Italy,

One by the President of the Swiss Confederation,

One by His Majesty the Emperor of Brazil;

Appointment of arbitrators

And the President of the United States, Her Britannic Majesty, His Majesty the King of Italy, the President of the Swiss Confederation, and His Majesty the Emperor of Brazil having respectively named their arbitrators, to wit:

The President of the United States, Charles Francis Adams, esquire;

Her Britannic Majesty, Sir Alexander James Edmund Cockburn, baronet, a member of Her Majesty's privy council, lord chief justice of England;

His Majesty the King of Italy, His Excellency Count Frederick Sclopis, of Salerano, a knight of the Order of the Annunciata, minister of state, senator of the Kingdom of Italy;

The President of the Swiss Confederation, M. James Stämpfli;

His Majesty the Emperor of Brazil, His Excellency Marcos Antonio d'Araujo, Viscount d'ltajubá, a grandee of the Empire of Brazil, member of the council of H. M. the Emperor of Brazil, and his envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary in France.

Organization of tribunal

And the five arbitrators above named having assembled at Geneva (in Switzerland) in one of the chambers of the Hôtel de Vill e on the 15th of December , 1871, in, conformity with the terms of the second article of the Treaty of Washington, of the 8th of May of that year, and having proceeded to the inspection and verification of their respective powers, which were found duly authenticated, the tribunal of arbitration was declared duly organized.

The agents named by each of the high contracting parties, by virtue of the same Article II., to wit:

For the United States of America, John C. Bancroft Davis, esquire;

And for Her Britannic Majesty, Charles Stuart Aubrey, Lord Tenterden, a peer of the United Kingdom, companion of the Most Honorable Order of the Bath, assistant under-secretary of state for foreign affairs;

[„I have long had a desire to visit the city where the Alabama Claims were settled by arbitration without the effusion of blood, where the principle of international arbitration was established, which I hope will be resorted to by other nations and be the means of continuing peace to all mankind.“

US President Ulysses S. Grant upon his visit in Geneva, Switzerland, July 1877 (Young, Around the World with General Grant, 1879, Vol 1, p.49 et seq.)]

Delivery of cases

Whose powers were found likewise duly authenticated, then delivered to each of the arbitrators the printed case prepared by each of the two parties, accompanied by the documents, the official correspondence, and other evidence on which each relied, in conformity with the terms of the third article of the said treaty.

Delivery of counter-cases

In virtue of the decision made by the tribunal at its first session, the counter-case and additional documents, correspondence, and evidence referred to in Article IV. of the said treaty were delivered by the respective agents of the two parties to the secretary of the tribunal on the 15th of April, 1872, at the chamber of conference, at the Hôtel de Ville of Geneva.

Delivery of arguments

[The Geneva Conference - The Alabama Arbitration, painted circa 1873, by Charles Edouard Armand-Dumaresq]

The tribunal, in accordance with the vote of adjournment passed at their second session, held on the 16th December, 1871, re-assembled at Geneva on the 15th of June, 1872; and the agent of each of the parties duly delivered to each of the arbitrators, and to the agent of the other party, the printed argument referred to in Article V. of the said treaty.

Deliberations of tribunal

The tribunal having since fully taken into their consideration the treaty, and also the cases, counter cases, documents, evidence, and arguments, and likewise all other communications made to them by the two parties during the progress of their sittings, and having impartially and carefully examined the same,

Has arrived at the decision embodied in the present award:

Whereas, having regard to the VIth and Vllth articles of the said treaty, the arbitrators are bound under the terms of the said Vlth article, 'in deciding the matters submitted to them, to be governed by the three rules therein specified and by such principles of international law, not inconsistent therewith, as the arbitrators shall determine to have been applicable to the case;

Definition of due diligence

And whereas the 'due diligence' referred to in the first and third of the said rules ought to be exercised by neutral governments in exact proportion to the risks to which either of the belligerents may be exposed, from a failure to fulfil the obligations of neutrality on their part;

And whereas the circumstances out of which the facts constituting the subject-matter of the present controversy arose were, of a nature to call for the exercise on the part of Her

Britannic Majesty's government of all possible solicitude for the observance of the rights and the duties involved in the proclamation of neutrality issued by Her Majesty on the 13th day of May, 1861;

Effect of a commission

And whereas the effects of a violation of neutrality committed by means of the construction, equipment, and armament of a vessel are not done away with by any commission which the government of the belligerent power, benefited by the violation of neutrality, may afterwards have granted to that vessel; and the ultimate step, by which the offense is completed, cannot be admissible as a ground for the absolution of the offender, nor can the consummation of his fraud become the means of establishing his innocence;

Exterritoriality of vessels of war

And whereas the privilege of exterritoriality accorded to vessels of war has been admitted into the law of nations, not as an absolute right, but solely as a proceeding founded on the principle of courtesy and mutual deference between different nations, and therefore can never be appealed to for the protection of acts done in violation of neutrality;

Effect of want of notice

And whereas the absence of a previous notice can not be regarded as a failure in any consideration required by the law ot nations, in those cases in which a vessel carries with it its own condemnation;

Supplies of coal

And whereas, in order to impart to any supplies of coal a character inconsistent with the second rule, prohibiting the use of neutral ports or waters, as a base of naval operations for a belligerent, it is necessary that the said supplies should be connected with special circumstances of time, of persons, or of place, which may combine to give them such character;

Responsibility for acts of the Alabama

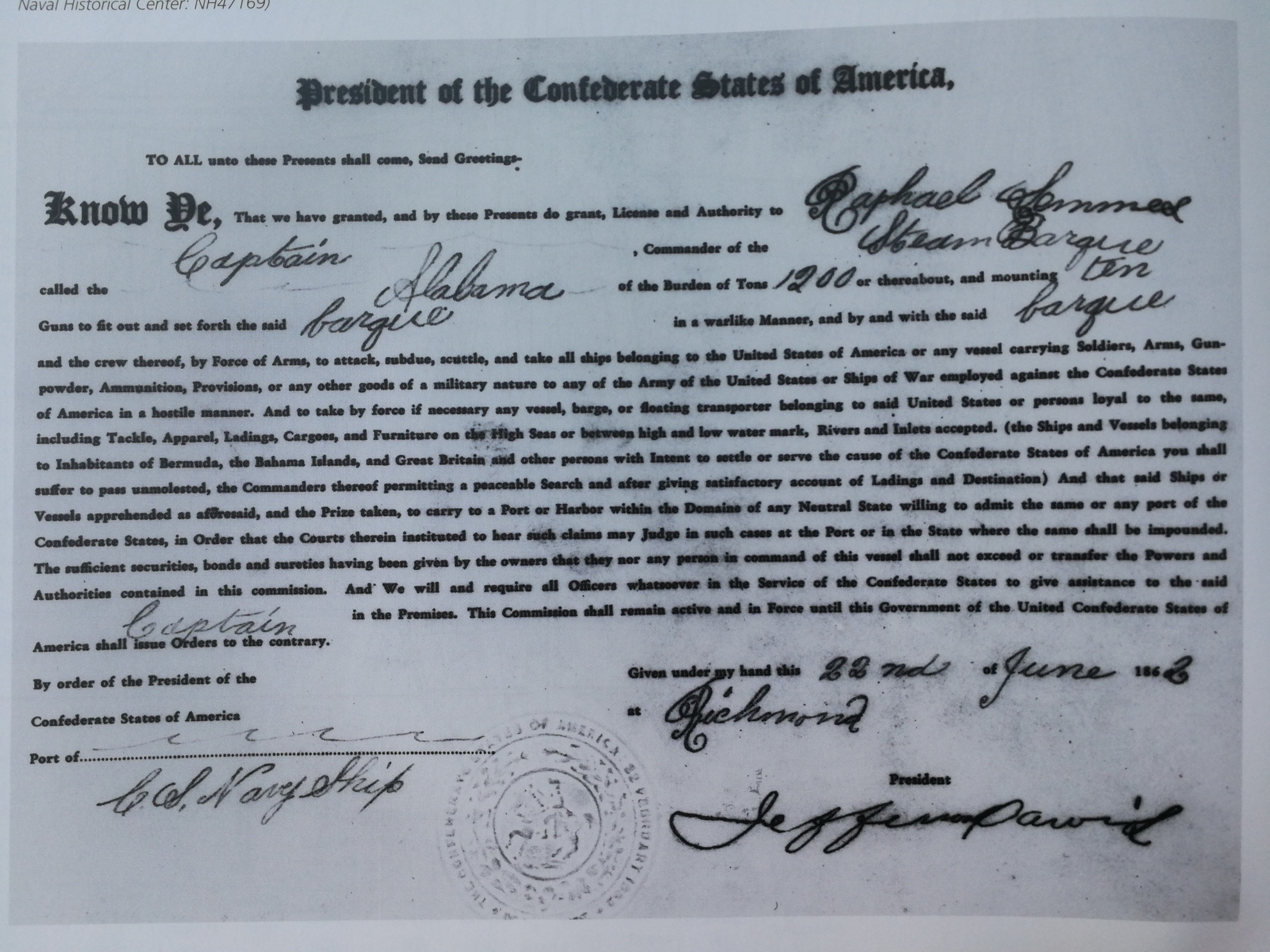

[A copy of the authorisation granted to Captain Raphael Semmes to attack US ships, signed by Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America and dated 22 June 1862. (US Naval Historical Center: NH47169).]

And whereas, with respect to the vessel called the Alabama, it clearly results from all the facts relative to the construction of the ship at first designated by the number '290' in the port of Liverpool, and its equipment and armament in the vicinity of Terceira through the agency of the vessels called the 'Agrippina' and the 'Bahama', dispatched from Great Britain to that end, that the British government failed to use due diligence in the performance of its neutral obligations; and especially that it omitted, notwithstanding the warnings and official representations made by the diplomatic agents of the United States during the construction of the said number '290', to take in due time any effective measures of prevention, and that those orders which it did give at last, for the detention of the vessel, were issued so late that their execution was not practicable; And whereas, after the escape of that vessel, the measures taken for its pursuit and arrest were so imperfect as to lead to no result, and therefore cannot be considered sufficient to release Great Britain from the responsibility already incurred.

And whereas, in despite of the violations of the neutrality of Great Britain committed by the '290,' this same vessel, later known as the confederate cruiser Alabama, was on several occasions freely admitted into the ports of colonies of Great Britain, instead of being proceeded against as it ought to have been in any and every port within British jurisdiction in which it might have been found;

And whereas the government of Her Britannic Majesty cannot justify itself for a failure in due diligence on the plea of insufficiency of the legal means of action which it possessed:

Four of the arbitrators, for the reasons above assigned, and the fifth for reasons separately assigned by him,

Are of opinion—

That Great Britain has in this case failed, by omission, to fulfill the duties prescribed in the first and the third of the rules established by the Vlth article of the Treaty of Washington.

And of the Florida

And whereas, with respect to the vessel called the 'Florida', it results from all the facts relative to the construction of the 'Oreto' in the port of Liverpool, and to its issue therefrom, which facts failed to induce the authorities in Great Britain to resort to measures adequate to prevent the violation of the neutrality of that nation, notwithstanding the warnings and repeated representations of the agents of the United States, that Her Majesty's government has failed to use due diligence to fulfil the duties of neutrality; And whereas it likewise results from all the facts relative to the stay of the 'Oreto' at Nassau, to her issue from that port, to her enlistment of men, to her supplies, and to her armament, with the cooperation of the British vessel 'Prince Alfred', at Green Cay, that there was negligence on the part of the British colonial authorities;

And whereas, notwithstanding the violation of the neutrality of Great Britain committed by the Oreto, this same vessel, later known as the confederate cruiser Florida, was nevertheless on several occasions freely admitted into the ports of British colonies;

And whereas the judicial acquittal of the Oreto at Nassau cannot relieve Great Britain from the responsibility incurred by her under the principles of international law; nor can the fact of the entry of the Florida into the confederate port of Mobile, and of its stay there during four months, extinguish the responsibility previously to that time incurred by Great Britain:

For these reasons,

The tribunal, by a majority of four voices to one, is of opinion—

That Great Britain has in this case failed, by omission, to fulfil the duties prescribed in the first, in the secondhand in the third of the rules established by Article VI. of the treaty of Washington.

And of the Shenandoah after leaving Melbourne

And whereas, with respect to the vessel called the 'Shenandoah' it results from all the facts relative to the departure from London of the merchant-vessel the ' Sea King' and to the transformation of that ship into a confederate cruiser under the name of the Shenandoah, near the island of Madeira, that the government of Her Britannic Majesty is not chargeable with any failure, down to that date, in the use of due diligence to fulfil the duties of neutrality;

But whereas it results from all the facts connected with the stay of the Shenandoah at Melbourne, and especially with the augmentation which the British government itself admits to have been clandestinely effected of her force, by the enlistment of men within that port, that there was negligence on the part of the authorities at that place:

For these reasons,

The tribunal is unanimously of opinion—

That Great Britain has not failed, by any act or omission, "to fulfil any of the duties prescribed by the three rules of Article VI. in the treaty of Washington, or by the principles of international law not inconsistent therewith", in respect to the vessel called the Shenandoah, during the period of time anterior to her entry into the port of Melbourne;

And by a majority of three to two voices, the tribunal decides that Great Britain has failed, by omission, to fulfil the duties prescribed by the second and third of the rules aforesaid, in the case of this same vessel, from and after her entry into Hobson's Bay, and is therefore responsible for all acts committed by that vessel after her departure from Melbourne, on the 18th day of February, 1865.

And of the Tuscaloosa, Clarence, Tacony, and Archer

And so far as relates to the vessels called—

The Tuscaloosa, (tender to the Alabama,)

The Clarence,

The Tacony, and

The Archer, (tenders to the Florida,)

The tribunal is unanimously of opinion—

That such tenders or auxiliary vessels, being properly regarded as accessories, must necessarily follow the lot of their principals, and be submitted to the same decision which applies to them respectively.

No responsibility for the Retribution, Georgia, Sunter, Nashville, Tallahassee, or Chickamauga

And so far as relates to the vessel called 'Retribution',

The tribunal, by a majority of three to two voices, is of opinion-

That Great Britain has not failed by any act or omission to fulfil any of the duties prescribed by the three rules of Article VI. in the treaty of Washington, or by the principles of international law not inconsistent therewith.

And so far as relates to the vessels called—

The Georgia,

The Sumter,

The Nashville,

The Tallahassee, and

The Chickamauga, respectively,

The tribunal is unanimously of opinion—

That Great Britain has not failed, by any act or omission, to fulfil any of the duties prescribed by the three rules of Article VI. in the treaty of Washington, or by the principles of international law not inconsistent therewith.

The Sallie, Jefferson Davis, Music, Boston, and V.H. Joy not taken into consideration

And so far as relates to the vessels called—

The Sallie,

The Jefferson Davis,

The Music,

The Boston, and

The V.H. Joy, respectively

The tribunal is unanimously of opinion—

That they ought to be excluded from consideration for want of evidence.

Claims for cost of pursuit not allowed

And whereas, so far as relates to the particulars of the indemnity claimed by the United States, the costs of pursuit of the confederate cruisers are not, in the judgment of the tribunal, properly distinguishable from the general expenses of the war carried on by the United States :

The tribunal is, therefore, of opinion, by a majority of three to two voices—

That there is no ground for awarding to the United States any sum by way of indemnity under this head.

And for prospective earnings

And whereas prospective earnings cannot properly be made the subject of compensation, inasmuch as they depend in their nature upon future and uncertain contingencies :

The tribunal is unanimously of opinion—

That there is no ground for awarding to the United States any sum by way of indemnity under this head.

Net freights only allowed

And whereas, in order to arrive at an equitable compensation for the damages which have been sustained, it is necessary to set aside all double claims for the same losses, and all claims for "gross freights", so far as they exceed 'net freights';

And whereas it is just and reasonable to allow interest at a reasonable rate;

And whereas, in accordance with the spirit and letter of the Treaty of Washington, it is preferable to adopt the form of adjudication of a sum in gross, rather than to refer the subject of compensation for further discussion and deliberation to a board of assessors, as provided by Article X. of the said treaty:

$ 15,500,000 compensation awarded

The tribunal, making use of the authority conferred upon it by Article VII. of the said treaty, by a majority of four voices to one, awards to the United States a sum of $15,500,000 in gold, as the indemnity to be paid by Great Britain to the United States, for

the satisfaction of all the claims referred to the consideration of the tribunal, conformably to the provisions contained in Article VII. of the aforesaid treaty.

The payment to be a bar

And, in accordance with the terms of Article XI. of the said treaty, the tribunal declares that "all the claims referred to in the treaty as submitted to the tribunal are hereby fully, perfectly, and finally settled."

Furthermore it declares, that "each and every one of the said claims, whether the same may or may not have been presented to the notice of, or made, preferred, or laid before the tribunal, shall henceforth be considered and treated as finally settled, barred, and inadmissible."

In testimony whereof this present decision and award has been made in duplicate, and signed by the arbitrators who have given their assent thereto, the whole being in exact conformity with the provisions of Article VII. of the said treaty of Washington.

Made and concluded at the Hôtel de Ville of Geneva, in Switzerland, the 14th day of the month of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and seventy-two.

CHARLES FRANCIS ADAMS.

FREDERICK SCLOPIS.

STÄMPFLI.

VlCOMTE D`lTAJUBÁ.

Sir Alexander Cockburn's Dissent

The paper which Sir Alexander Cockburn asked leave to have incorporated with the record was not annexed to the official protocol handed to the agent of the United States; but on the 24th of September 1872 there appeared in a supplement to the London Gazette a paper entitled "Reasons of Sir Alexander Cockburn for dissenting from the award of the tribunal of arbitration;" and a copy of this number of the Gazette was transmitted to the agent of the United States as the paper that should have been annexed to the protocol.1 After reading the document thus published, Mr. Fish declared that if the agent of the United States had had an opportunity to become acquainted with its contents at Geneva he doubtless would have felt it his "right and duty to object to the reception and filing of a paper which would probably not have been officially received by the tribunal had an opportunity been afforded to invite their attention to some of its reflections on this government and its agent and counsel."2 Occupying three times as much space as the opinions of all the other arbitrators together, and

almost twice as much as the Case of the United States, the paper dealt in sweeping and oftentimes violent criticisms of men and things, which even Sir Alexander Cockburn's colleagues did not wholly escape. While he described himself in two places as sitting on the tribunal "as in some sense the representative of Great Britain,"3 he deprecated the limitations imposed upon the arbitrators by the rules of the treaty;4 represented Mr. Staempfli as maintaining that "there is no such thing as international law," and that the arbitrators were to proceed "according to some intuitive perception of right and wrong, or speculative notions of what the rules as to the duties of neutrals ought to be;"5 charged counsel of the United States with "the most singular confusion of ideas, misrepresentation of facts, and ignorance, both of law and history, which were perhaps ever crowded into the same space," and with affronting the tribunal by attempting to "practice" on its "supposed credulity or ignorance;"6 and animadverted upon the Case of the United States as seeming " to pour forth the pent-up venom of national and personal hate."7

That Sir Alexander Cockburn deemed it incumbent upon him, as a member of a tribunal judicial in its nature, before which his government was ably represented by an agent and counsel, to adopt the tone of partisan controversy betrayed a defect in judgment as well as in temper. In speaking as a member of the tribunal of arbitration he ought at least to have remembered that the weight which an expression of opinion derives from the judicial position of him who utters it is worse than lost when the speaker proclaims, by word or by act, that he has put off the character of the judge for that of the advocate. No doubt the feeling of resentment which Sir Alexander Cockburn professed, on account of the charges of hostile motives and insincere neutrality made in the American Case, was genuine. But in its Counter Case the British Government distinctly refused to reply to these charges, saying that if they were of any weight or value the proper reply to them would be found in the proofs. If the British Counter Case and the British argument were defective because they were free from vituperation, it was not the place of an arbitrator to attempt to supply the omission. Nor should Sir Alexander Cockburn have for-

gotten that in the case of the Alabama whose career formed the type, just as her name afforded the description, of the Confederate cruisers and their depredations, the evidence was so overwhelming that he himself, while maintaining that " a mere error in judgment" did not amount to negligence, was compelled to declare that it was " impossible to say that in respect of this vessel there was not an absence of 'due diligence' on the part of the British authorities."8

Arbitrators' Expressions as to British Feeling

In this relation it is proper to advert to the opinions of the arbitrators on the question of British feeling toward the United States during the civil war.The only arbitrator, except Sir Alexander Cockburn, who undertook specially to discuss this question was Count Sclopis: but there are expressions on various aspects of the subject in the opinions of the other arbitrators. Count Sclopis, while "far from thinking that the animus of the English Government was hostile to the Federal Government during the war," said that " there were moments when its watchfulness seemed to fail and when feebleness in certain branches of the public service resulted in great detriment to the United States." The circumstances during the first years of the war—the establishment of Confederate agencies in England, the presence and reception of Confederate representatives, the interests of great commercial houses at Liverpool where opinion was openly pronounced in favor of the South, and public expressions, even by the Queen's ministers, as to the improbability of the reestablishment of the Union—were, he thought, such as must have influenced, if not the government itself, at least a part of the population. Under

these circumstances, and in view of the dangers to which the United States was exposed in Great Britain and her colonies, the government should, in his opinion, have fulfilled its duties as a neutral " by the exercise of a diligence equal to the occasion."9 As to the existence or nonexistence of unfriendly feeling, Viscount d'Itajubá expressed no opinion; but in speaking of the duty of a neutral to detain a vessel which had departed in violation of its neutrality, when such vessel came again within its jurisdiction, he said: "By seizing or detaining the vessel the neutral only prevents the belligerent from deriving advantage from the fraud committed within its territory by the same belligerent; while, by not proceeding against a guilty vessel, the neutral justly exposes itself to having its good faith called in question by the other belligerent."10 Sir Alexander Cockburn himself, while denying the existence of partiality or of willful negligence on the part of the British Government, declared that, "though partiality does not necessarily lead to want of diligence, yet it is apt to do so, and in a case of doubt would turn the scale."11 At various places, in the cases of the Florida, the Alabama, the Shenandoah, and the Retribution, Mr. Adams resorted to evidences of sympathy with the Confederacy on the part of the local officials as an explanation of the lack of due diligence shown on certain occasions. Especially is this so in respect of the action of the customs authorities at Liverpool in the cases of the Florida and the Alabama, and of the authorities in the Bahamas in the cases of the Florida and the Retribution. But as to the British Government itself, he expressed the opinion that its failure to adopt adequate measures to prevent the escape of the Florida and the Alabama from England was due to the conception which it entertained in the earlier stages of the war, that its obligations as a neutral were discharged by the pursuit of a passive policy—a policy that stopped with the investigation of evidence furnished by agents of the United States, and originated no active measures of prevention. "Much as I may see cause," said Mr. Adams in his opinion in the case of the Florida, "to differ with him (Lord Russell) in his limited construction of his own duty, or in the views which appear in these papers to have been taken by him of the policy proper to be pursued by Her Majesty's government, I am far from drawing

any inferences from them to the effect that he was actuated in any way by motives of ill will to the United States, or indeed by unworthy motives of any kind. If I were permitted to judge from a calm comparison of the relative weight of his various opinions with his action in different contingencies, I should be led rather to infer a balance of good will than of hostility to the United States."12

Attitude of Mr. Adams

The attitude of Mr. Adams as a member of the tribunal of arbitration merits more than passing notice. To say that the neutral arbitrators performed their duty with intelligence and impartiality is only to do them justice; but they had no temptation to be partial. But Mr. Adams was appointed by one of the parties to the controversy, and each opinion that he expressed directly affected the interests of his own government. Yet, after following his course through published and unpublished records, from the time of his appointment as arbitrator till he signed the award at Geneva, I venture to say that on no occasion did he betray a spirit of partiality. This fact appears the more remarkable when we consider that the very questions on which it finally became his duty to pronounce judgment were discussed by him through a long and exciting period of contention as the diplomatic representative of the United States.

His conception of his office was expressed in one of his opinions. " The arbitrators," he said, "appear to me at least to have a duty to the parties before the tribunal to state their convictions of the exact truth without fear or favor."13 Guided by a clear, accurate, and discriminating perception, Mr. Adams performed this duty with the utmost fidelity; and at the conclusion of his labors he received the commendation of Her Majesty's government14 as well as of his own.15

Reception of the Award by the Public

In the United States the award of the tribunal was received with satisfaction though during the pendency of the proceedings the course of the government, especially in regard to the presentation of the indirect claims, was made the subject of attacks which the progress of a Presidential contest did not tend to mollify.16 In England public opinion, as reflected by the press, was somewhat divided, it being influenced, no doubt, as in the United States, to some extent by party feeling. The Times viewed the settlement of the question with profound satisfaction17, while the Standard was fierce in denunciation of it.18 The Telegraph declared that the victory had been magnificent, though it was England that must pay the bill.19 The Saturday Review thought the result "profoundly mortifying to Englishmen." The Daily News said that the arbitrators had done better for the parties than they could have done for themselves.20 The Morning Post referred to the whole transaction as "a bungled unsettling settlement."21 The Morning Advertiser characterized what was said in defense of the treaty and arbitration as "wild, sentimental rubbish." The London Observer hailed the award as a triumph of the cause of peace22. The Nonconformist said that the Geneva arbitration had rendered a service to civilization.

Annex:

Speech of the Chairman at the press conference after the award was signed

(Hackett, Reminiscences of the Geneva Tribunal of Arbitration, 1872, the Alabama Claims, 1911, at 343 et seq.)

"Gentlemen, and honored colleagues:—

"Our work is done. The Court of Arbitration has lived its life. During its existence the best relations have constantly been maintained among us. In all that concerns myself, I cannot sufficiently express to you, gentlemen, the gratitude I feel in having been supported by your indulgence and intelligence in the exercise of the delicate functions which you were pleased to confer upon me.

"We have been fortunate in beholding the complete success obtained by the first part of our work regarded solely from an official point of view. No more flattering eulogium could have been conferred on us than that which has been expressed by the highest authorities of the two countries interested. They recognize that we have acted as the devoted friends of both powers. Such has been in fact the real and prolonged sentiment which animated us in the second part of our work, confined, as

it has been, entirely within the limits of the judicial authority conferred upon us by the Treaty of Washington.

"We have employed a scrupulous care and absolute impartiality in order not to deviate for an instant from the rules of justice and equity. The cooperation of the eminent jurists who assisted the two Governments, as well as of the Agents who represented them, has powerfully aided us in this work; and we are happy to be able to offer them all our sincere thanks. We have the testimony of our conscience that we have not failed in our duty. We express the fervent prayer that God will inspire all Governments with the constant purpose of maintaining that which is the invariable desire of all civilised people, that which is, in the order of the moral as well as the material interests of society, the highest of all good, — peace.

"Our last word shall be for Geneva, this noble and hospitable city, which has received us so well; and in bidding it farewell we can assure it that its remembrance will never be effaced from our minds. The Tribunal thought that it might be agreeable to the Government of the Republic to possess among its archives a testimony of what has on this occasion taken place in the Hôtel de Ville. It has, therefore, commanded a copy of the judgment, signed by all the members, to be deposited in the archives of the Conseil d'État. Once more we take leave of the city of Geneva. We wish it all the happiness that it merits."

1Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 48.

2Id. 546 547.

3Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington. IV. 286, 313.

4Id. 231.

5Id. 233.

6Id. 286

7Id. 311

8Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 459,460. Mr. Cushing, in his Treaty of Washington, 128, states that Sir Alexander Cockburn, as soon as the tribunal was declared dissolved, abruptly left the room "without a word or sign of corteous recognition for any of his colleagues," and "disappeared in the manner of a crimininal escaping from the dock, rather than of a judge seperating, and that forever, from his colleagues of the bench;" and he then proceeds to characterize Sir Alexander´s conduct and "dissenting opinion" in terms of which the forgoing comparison furnishes an example. A leading journal, in a review of Mr. Cushing´s book, observed that, while the British arbitrator´s conduct was irregular and unsuitable, Mr. Cushing might have shown the fact without resorting to "invectives."(Rev. de Droit Int. VI. 154.) Sir Alexander´s "irregularities" were indeed little commended, but much censured in the London press. (Cushing´s Treaty of Washington, 130, et seq.)

9Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV.9.

10Id. 97-98.

11Id. 313.

12Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 162. Cobden, in a letter to Sumner of May 2, 1863, touching the fitting out of Confederate cruisers in England, said: "I have reason to know that our government fully appreciates the gravity of this matter. Lord Russell, whatever may be the tone of his ill-mannered despatches, is sincerely alive to the necessity of putting an end to the equipping of ships of war in our harbors to be used against the Federal Government by the Confederates. He was bona fide in his aim to prevent the Alabama from leaving, but he was tricked and was angry at the escape of that vessel. * * * If Lord Russell's despatches to Mr. Adams are not very civil he may console himself with the knowledge that the Confederates are still worse treated." (Am. Hist. Rev. II. 310.) In the same letter Cobden stated that he had urged Lord Russell to be " more than passive in enforcing the law respecting the building of ships for the Confederate government, I especially referred to the circumstance that it was suspected that some ships pretended to be for the Chinese Government were really designed for that of Richmond, and I urged him to furnish Mr. Adams with the names of all the ships building for China and full particulars where they were being built. This Lord Russell tells me he had already done, and he seems to promise fairly. Our government are perfectly well informed of all that is being done for the Chinese."

13Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 228.

14Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, II. 584.

15Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 546. See, for acknowledgements of the services of the neutral arbitrators, For.Rel. 1872, pp. 109, 320, 648.

16Mr. Fish and the Alabama Claims , 104.

17September 9, 10, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 23.

18September 10, 12, 16, 17, 18.

19September 9, 16, 17.

20September 9, 16.

21September 9.

22September 8.

1Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 48.

2Id. 546 547.

3Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington. IV. 286, 313.

4Id. 231.

5Id. 233.

6Id. 286

7Id. 311

8Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 459,460. Mr. Cushing, in his Treaty of Washington, 128, states that Sir Alexander Cockburn, as soon as the tribunal was declared dissolved, abruptly left the room "without a word or sign of corteous recognition for any of his colleagues," and "disappeared in the manner of a crimininal escaping from the dock, rather than of a judge seperating, and that forever, from his colleagues of the bench;" and he then proceeds to characterize Sir Alexander´s conduct and "dissenting opinion" in terms of which the forgoing comparison furnishes an example. A leading journal, in a review of Mr. Cushing´s book, observed that, while the British arbitrator´s conduct was irregular and unsuitable, Mr. Cushing might have shown the fact without resorting to "invectives."(Rev. de Droit Int. VI. 154.) Sir Alexander´s "irregularities" were indeed little commended, but much censured in the London press. (Cushing´s Treaty of Washington, 130, et seq.)

9Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV.9.

10Id. 97-98.

11Id. 313.

12Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 162. Cobden, in a letter to Sumner of May 2, 1863, touching the fitting out of Confederate cruisers in England, said: "I have reason to know that our government fully appreciates the gravity of this matter. Lord Russell, whatever may be the tone of his ill-mannered despatches, is sincerely alive to the necessity of putting an end to the equipping of ships of war in our harbors to be used against the Federal Government by the Confederates. He was bona fide in his aim to prevent the Alabama from leaving, but he was tricked and was angry at the escape of that vessel. * * * If Lord Russell's despatches to Mr. Adams are not very civil he may console himself with the knowledge that the Confederates are still worse treated." (Am. Hist. Rev. II. 310.) In the same letter Cobden stated that he had urged Lord Russell to be " more than passive in enforcing the law respecting the building of ships for the Confederate government, I especially referred to the circumstance that it was suspected that some ships pretended to be for the Chinese Government were really designed for that of Richmond, and I urged him to furnish Mr. Adams with the names of all the ships building for China and full particulars where they were being built. This Lord Russell tells me he had already done, and he seems to promise fairly. Our government are perfectly well informed of all that is being done for the Chinese."

13Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 228.

14Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, II. 584.

15Papers relating to the Treaty of Washington, IV. 546. See, for acknowledgements of the services of the neutral arbitrators, For.Rel. 1872, pp. 109, 320, 648.

16Mr. Fish and the Alabama Claims , 104.

17September 9, 10, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 23.

18September 10, 12, 16, 17, 18.

19September 9, 16, 17.

20September 9, 16.

21September 9.

22September 8.